Brussels, 13 January 2022

On 15 September 2021, European Commission President von der Leyen announced in her State of the Union address that the European Commission will propose to make 2022 the European Year of Youth, “a year dedicated to empowering those who have dedicated so much to others”. The overall objective is to “boost the efforts of the Union, the Member States, regional and local authorities to honour, support and engage with youth in a post-pandemic perspective”.

Support to youth employment

Among the priorities, the European Year of Youth will emphasise the “employment opportunities for youth in the post-pandemic recovery through the reinforced Youth Guarantee”. The European Youth Guarantee, adopted by the Council of the EU in October 2020, aims to facilitate the access to education and employment of young people. As the unprecedented crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic affected young people disproportionally, the reinforced Youth Guarantee set up a comprehensive job support available to young people at risk of unemployment unable to enter today’s labour market. In March 2021, the European Parliament adopted its Guidelines for the 2022 Budget – Section III, with a similar focus on the youth. The Resolution calls for “all funding possibilities [to be] fully explored in order to successfully improve labour market inclusion, in particular via vocational training, measures to improve social inclusion, working conditions and social protection, including for persons with disabilities, as well as family and life prospects for young people, taking into account the work-life balance directive”.

Is work the only thing young people only want?

Access to employment and career prospects are key for young people to become financially independent and fulfill their work goals. However, work is not only a goal, but also a mean to fulfill more important life projects, such as to start a family. Yet, as highlighted in a European Commission Report on the Impact of Demographic Change, the European declining birth rate (in 2018, European women had in average 1.55 children, below the population replacement level of 2,1) and the increase in age of parents when having their first child (between 2001 and 2018, the mean age of women at childbirth in the EU went from 29.0 to 30.8) seems to demonstrate that having children is not anymore a priority for young people.

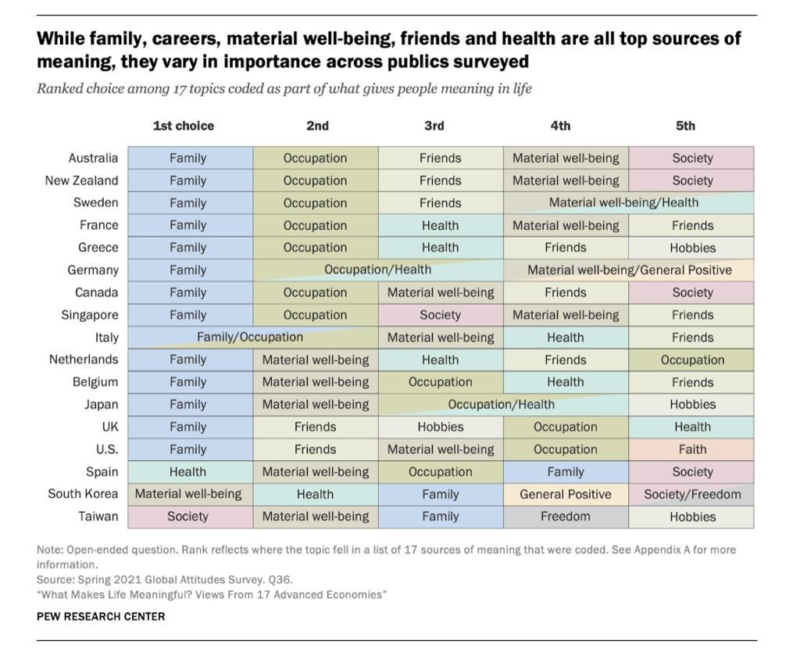

Looking into the data, it is actually not the case: in France for example, the wish for children remains stable in time, with 2.39 children desired per families, a number way above the replacement rate. Rather, this “child gap” is explained by the difficulties and the obstacles young couples face, not their wish for a family. Overall, family remains the main source of meaning for people worldwide:

When addressing the needs and the hopes of young people, the European Commission should also answer to their attachement to family, and their wish to start one. It is of a double interest, as family well-being increases work productivity, life satisfaction and the overall social cohesion of communities.